Elio Fiorucci: bringing the spirit of Carnaby Street to the world. Photograph: A Roveri (Archivio Mondadori)

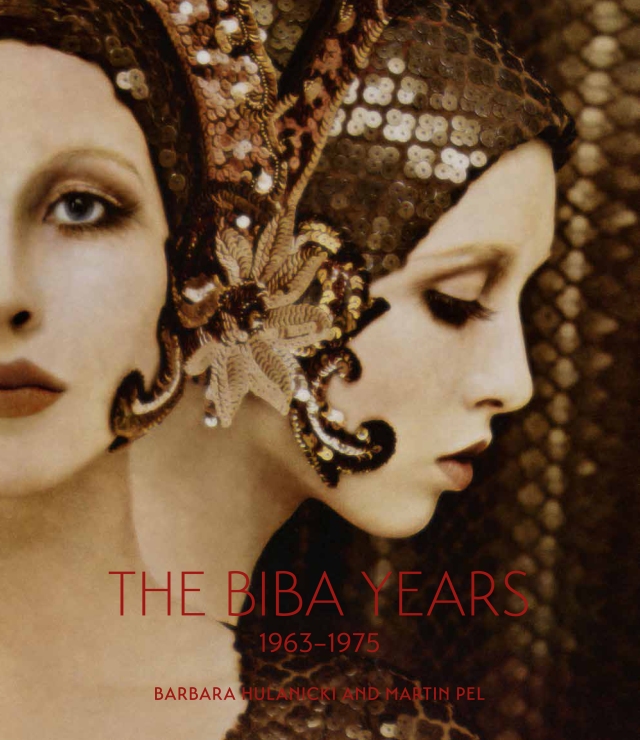

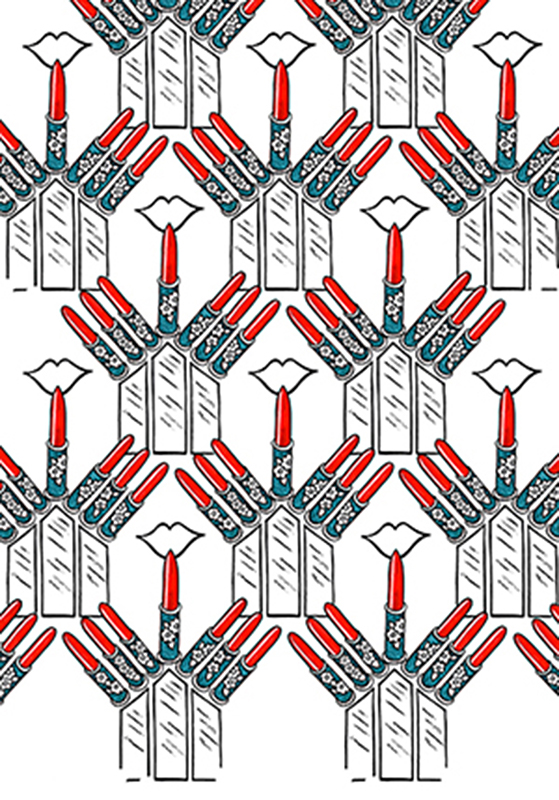

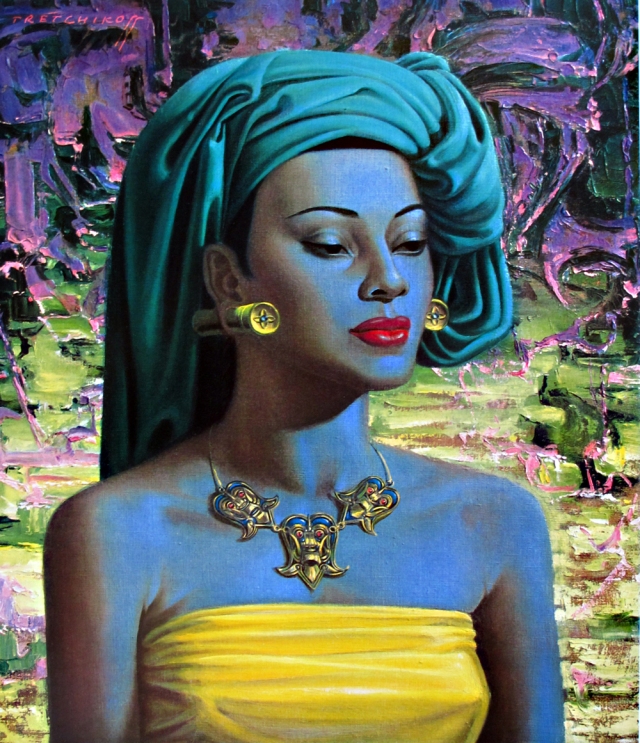

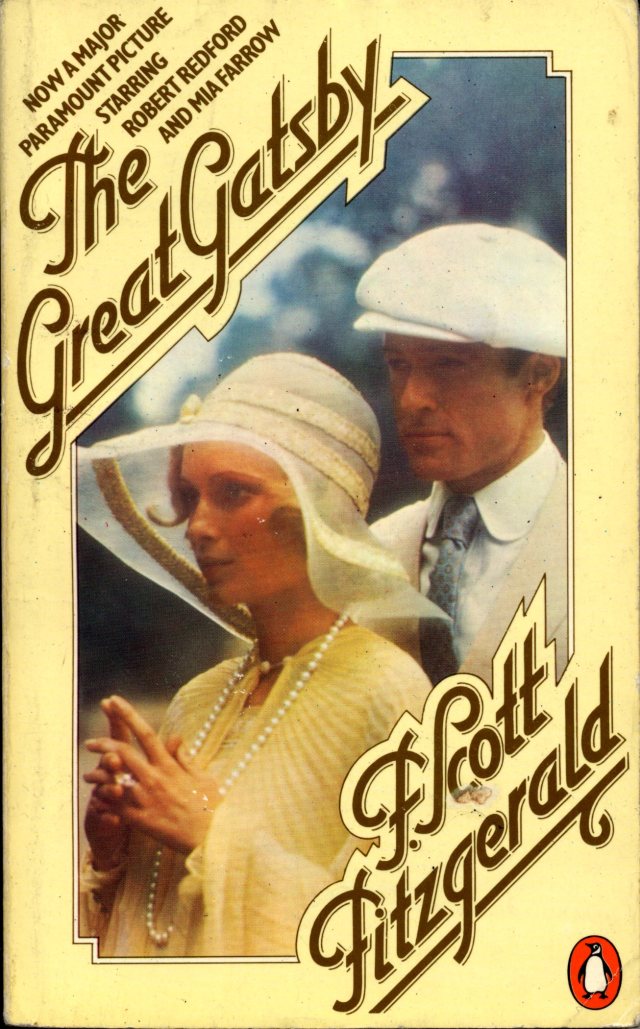

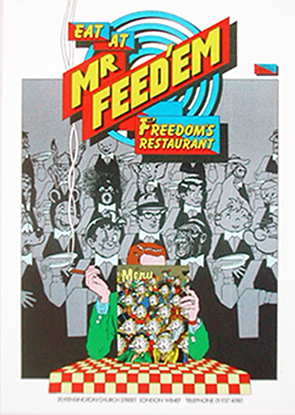

We were very sad to hear of the recent death of Elio Fiorucci, one of the most radical and influential designers of the 70s, who perfectly captured the decade’s spirit of diversity and self-expression in his string of shops from Milan to New York to London – fashion and lifestyle emporiums that doubled as destinations in which to see and be seen, hang out and party. Like the London stores he was inspired by – particularly Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba and Tommy Roberts’s Mr Freedom – Fiorucci’s fun, flashy, irreverent designs collaged pop culture iconography and cribbed from various decades, combining 40s glamour, 50s kitsch and 60s youthquake with keenly sourced inspirations from around the ever-shrinking globe, prompting the label’s biographer Eve Babitz to describe it as ‘the whole 20th century in one place’.

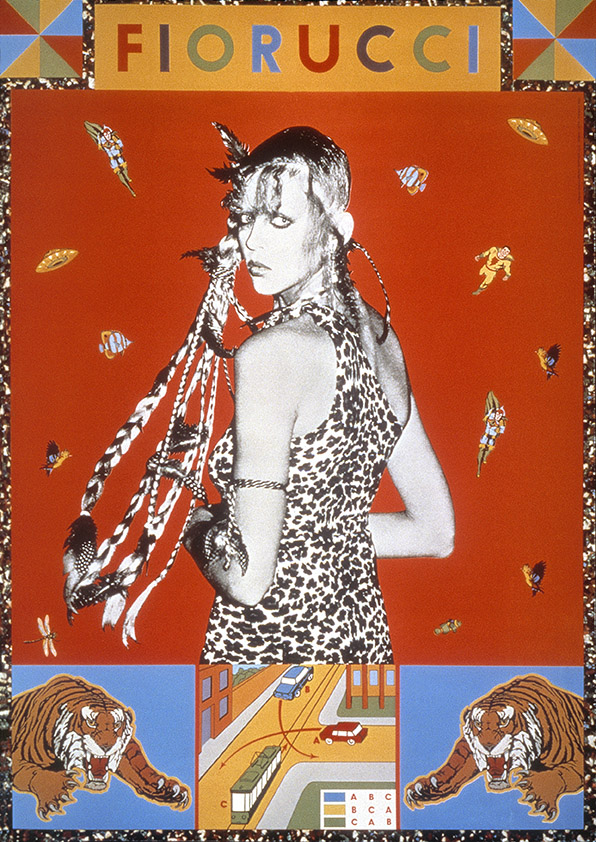

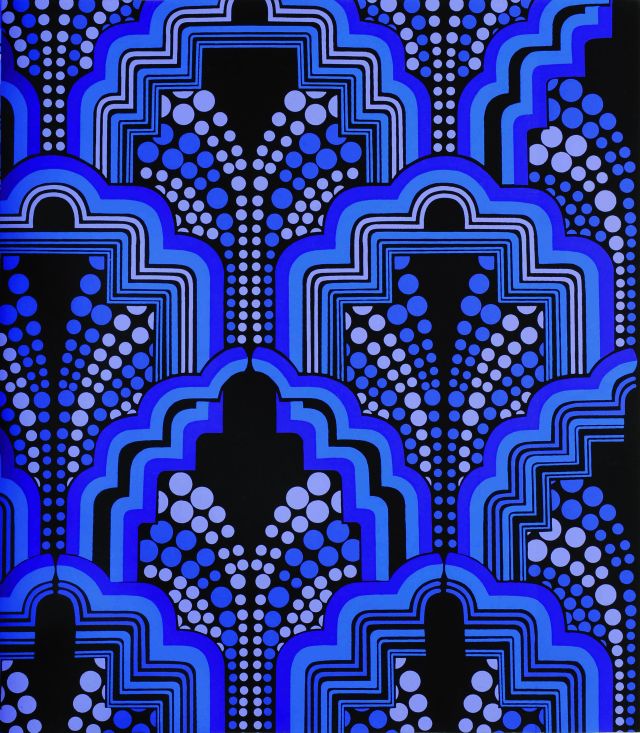

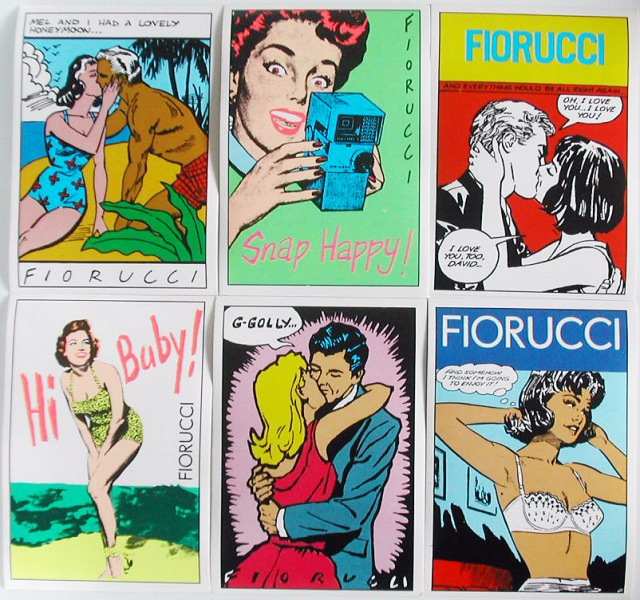

An advertising poster displays Fiorucci’s pop culture pick ‘n’ mix: UFOs, 50s kitsch, disco, old Hollywood… Photograph copyright of Edwin Co Ltd

And it was a place everyone wanted to be: famously Fiorucci’s New York store attracted everyone from Hollywood to bonafide royalty, rock stars, presidents’ wives, and the starry crowd who frequented the legendary nightclub Studio 54, not to mention the daring individuals in synch with the decade’s anything goes, do-your-own thing zeitgeist, which also drove the label’s creator.

A party at the New York store in the 70s – it was a magnet for the famous and fabulous, from Andy Warhol and Debbie Harry to cool club kids. Photo courtesy of Franco Marabelli

When we were researching our book 70s Style & Design we were lucky enough to interview this fashion luminary about his work in the context of the decade’s key trends. Here it is…

We’ve read that you wanted to bring the spirit of Carnaby Street to Milan, and that you were influenced by Biba (as a lifestyle emporium) and Tommy Roberts’s fashion label Mr Freedom, whose pop sensibility and collaging of eras echoed that of Fiorucci’s designs. What drew you to London in the late 60s and how did it differ from Milan? Milan seems to have been very creative too, with designers such as Ettore Sottsass, Archizoom, etc.

During my first inspiring trip to London in 1964 I was struck by the radical changes in lifestyle and fashion trends. What I liked most was the Biba shop. I fell in love with its attention to detail; with the quality and honest price of every product – it was revolutionary! Also important were Carnaby Street, Ossie Clark and Zandra Rhodes.

In Milan, yes, we had Sottsass, Achille Castiglioni, Archizoom and Alessandro Mendini, who were making radical changes in the design world, but there wasn’t a fashion scene like there was in London.

One of our book’s key themes is the backlash against polite, pared-down modernism by the pop movement. By the 70s the reaction against modernism’s restrictive visual vocabulary had led to designs that were expressive, ironic, fun, and challenged traditional notions of ‘good’ taste – for example the designs of Mendini and Sottsass, Mr Freedom and, of course, Fiorucci. Were you reacting against consistent, conservative design?

Yes, pop culture has been fundamental in my life, because it rejected conservatism, and instinctively I rejected conservative Italian culture. The 70s saw a global liberation of aesthetics that challenged the norms of every previous model.

One challenge to conventional ideas of ‘good’ design during the 70s was a very knowing use of kitsch, marked by the publication of Gillo Dorfles’s book on the subject in the late 60s and borne out (for example) by the presence of a Kitsch room at Big Biba in the early 70s. Was this something that influenced you?

I consider Gillo Dorfles a real luminary. He had a huge influence on the perception of aesthetics in Italy and the rest of the world with his uncompromising vision.

Our book also covers the cultural pluralism that emerged during the 70s, of which Fiorucci is a great example, taking inspiration from different decades, cultures and countries…

My role of global researcher – a proto ‘coolhunter’ – along with my shops in Galleria Passarella and Via Torino in Milan (where there was an area for cultural and musical performances), was a wonderful opportunity to present a mix of objects, music, food, perfumes, etc, from around the world.

Would you say that people were beginning to demand the kind of thing that Fiorucci was offering? Were attitudes to design changing? We get the impression that the 70s were a decade when people began to express themselves more through their clothes and surroundings and individuality was cherished. Do you agree with this?

Yes, the 70s freed people from conventions in dress and lifestyle, giving them the confidence to create their own personal style. The Fiorucci shops coincided with this. It was a fortuitous coincidence, but not really chance. I was in touch with the decade’s noncomformist zeitgeist.

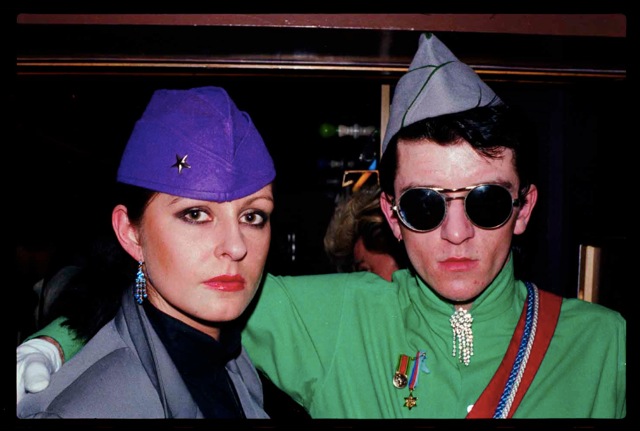

The New York store’s glamorous staff showcase the label’s diverse influences, from army surplus to 50s sci-fi. Photo courtesy of Raina Sachs

Our book will be covering the High-tech movement in interiors and the reinvention of utility wear and army surplus as fashion, something Fiorucci was an early adopter of. Tell us about this.

Yes Fiorucci reappropriated utility clothing, sportswear, military wear as fashion/street wear – a trend that continues today. The success of army surplus was exceptional: we sold about 3,000 pairs of American marine fatigue pants in one month, and these determined a trend in menswear for a long time.

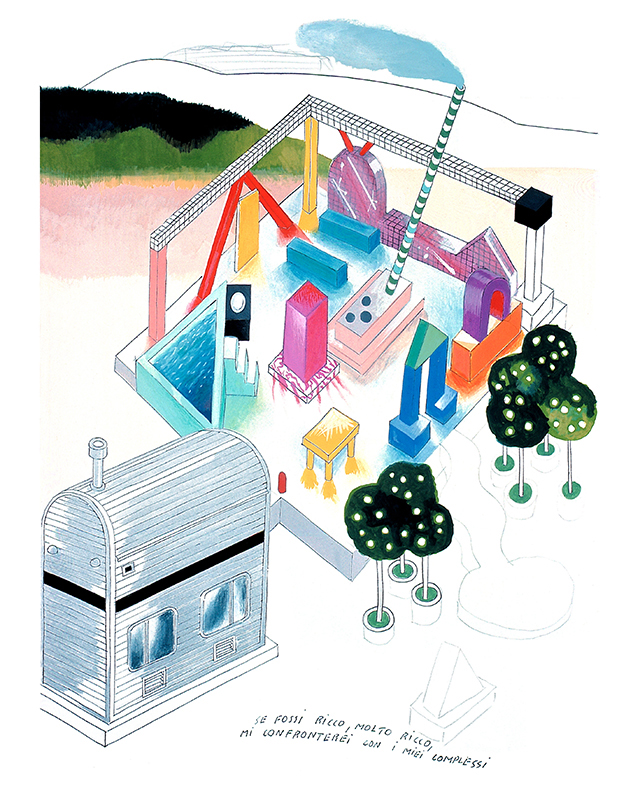

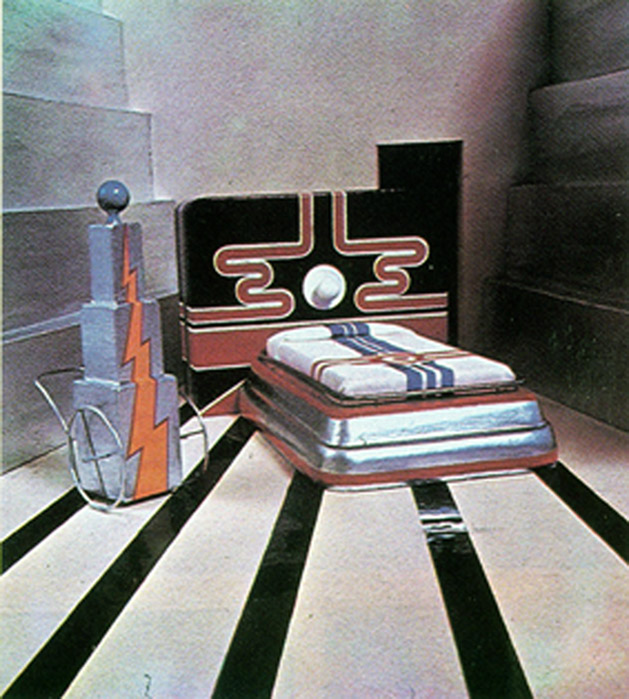

You were also very ahead of your time in that your shops had High-tech interiors. What got you into the High-tech style generally? Were you influenced by designers such as Bruno Munari?

In my 40 years of activity in my shop in Galleria Passarella I experimented with every kind of furniture – from Amalia Del Ponte minimalism [she made geometric Plexiglass sculptures] to English Pop, to the work of graffiti artist Keith Haring, who transformed my shop in an artwork. Fiorucci’s High-tech period was quite short-lived because every two to three years I felt the need to change the shop’s style.

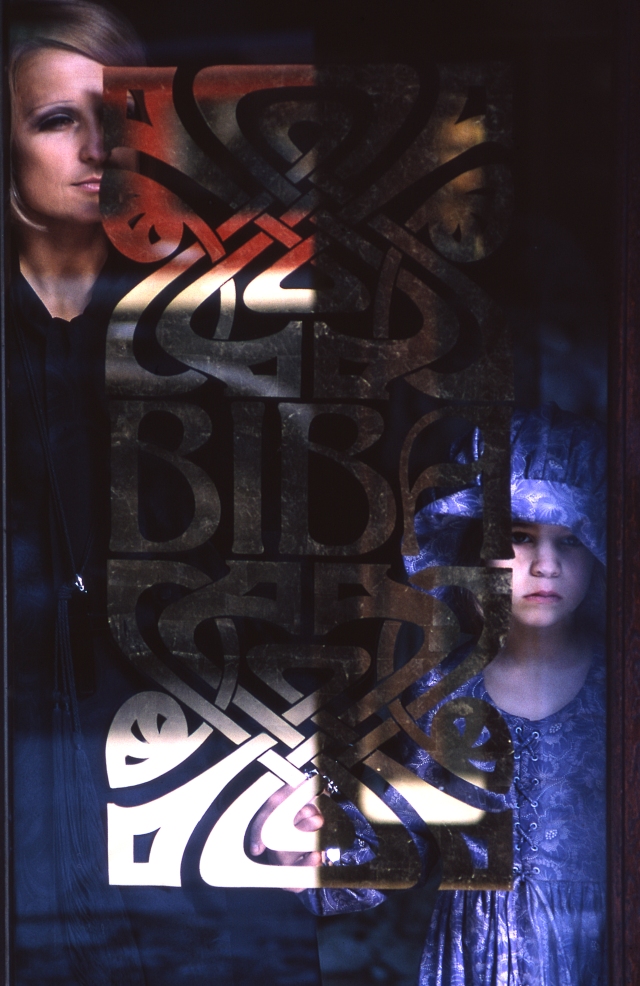

The window of Fiorucci’s New York store, designed by Kit Grover circa 1978, reflects the era’s High-tech trend. Photo courtesy of Kit Grover

Similarly, in a fashion context, you took industrial items like toolboxes and safety goggles and reinvented them as handbags and sunglasses. Was this related to your interest in High-tech and its placing of industrial objects in a domestic or non-industrial context?

I was immersed in a revolutionary culture in which conventions were called into question: why couldn’t a jute sack normally used for onions also be a tote bag? Why couldn’t a material like polythene be used for sandals? Why couldn’t the American hydraulics bag, carpenter’s belt and work shoes be part of a comfortable, functional fashionable wardrobe, just as jeans had been?

An advert for Fiorucci’s Safety Jeans featuring a pair of original painter’s overalls from the 1920s in an homage to utility clothing, one of the many inspirations of the label. From Fiorucci The Book by Eve Babitz

Your collaging of eras and cultural references has led some to describe you as a postmodernist. Do you agree with this?

I don’t feel I belong to any movement in particular. I had the luck to live during a very interesting period of the 20th century, after a devastating war when there was the need to rebuild a new world, new values and a new life philosophy.

Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren had a similar approach to you, playing with a range of stylistic vocabularies – from 50s revivalism to fetish gear as street wear – via their succession of shops: Let it Rock, Sex, Seditionaries, etc. Did they make an impression on you? We know she is a fan of yours.

I consider Vivienne Westwood a great artist and she was a great teacher to me. She appreciated my vision of change.

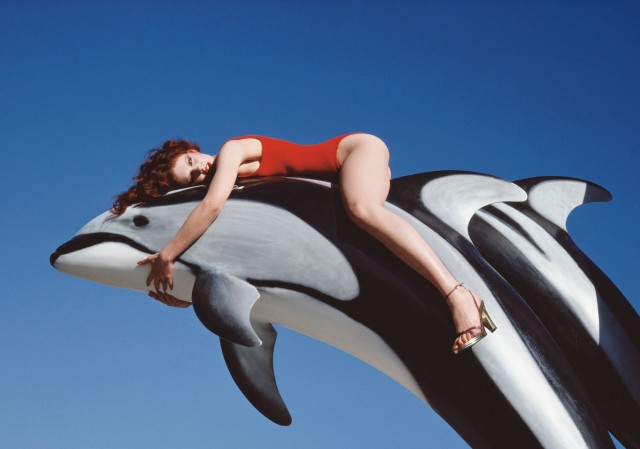

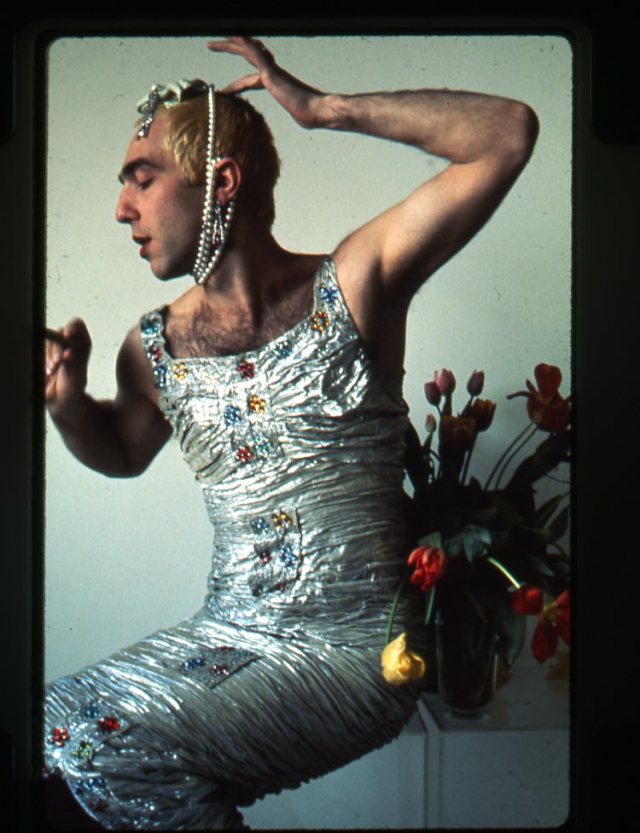

Sexiness is another of Fiorucci’s defining qualities. Was this influenced by the more libertarian attitudes that were emerging in the late 60s?

Eroticism is one of the most repressed drives in our culture. Free love, as an act of communion, is desirable. I think that with the end of fear love can begin, which will be joyful for all humanity.

What was the inspiration behind Fiorucci’s plastic clothing and accessories? Was this a nod to the fun, throwaway fashion of the pop 60s?

Plastic is one of the most important inventions for humanity. It totally changed our way of life. It is beautiful, tactile, useful.

A pair of platforms piles on the pop culture references, from Carmen Miranda’s 40s kitsch to 30s Ferragamo and 70s glam, all in glorious plastic

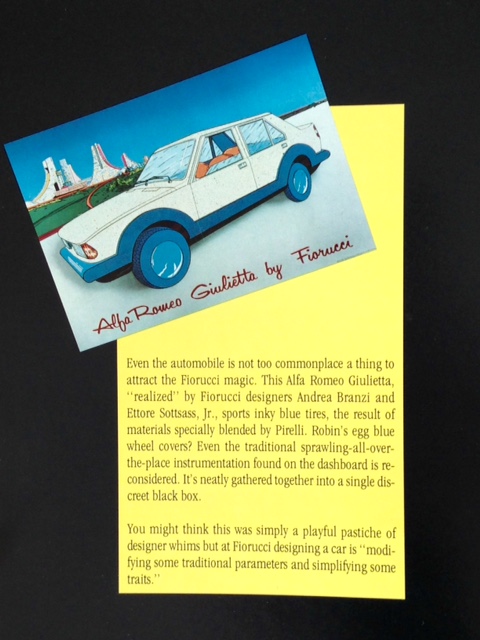

Eve Babitz’s Fiorucci book mentions that Andrea Branzi and Ettore Sottsass collaborated with the label – it has a picture of an Alfa Romeo Giulietta that they redesigned for you, for example. Could you tell us more about your collaborations with them?

The Alfa Romeo Giulietta was redesigned by Ettore and Andrea. Unfortunately it was so innovative that the parent company, frightened, didn’t put it in production. Ettore Sottsass, Andrea Branzi and Franco Marabelli designed my shop on 59th street in New York.

We know that Fiorucci’s New York store was one of the places to go, along with Studio 54. What made Fiorucci so irresistible to people like Andy Warhol and the Studio 54 crowd?

The opening of the New York Fiorucci shop and, one year later, Studio 54 happened during a very special period. After London, New York was becoming the capital of the lifestyle revolution. Free-thinking people were looking for a place to experiment and New York was a magnet. It was no accident that Studio 54 – emblem par excellence of the disco phenomenon – opened in the heart of Manhattan.

In terms of Fiorucci’s fabulous graphics, were you and Franco Marabelli aware of UK graphic designers such as Barney Bubbles, Mike Haggerty and George Hardie? And the work of West Coast graphic designer April Greiman?

Yes, we knew of them but we didn’t delve deep. Our research spectrum was less specific, more instinctive. We visited the whole world, picking up antique/modern/ethnic objects. There were no rules, only, ‘Do we like it or not?’ Maybe this was the secret of Fiorucci’s success…